Das Klavier, part 3. From: Mozart. Sein Charakter, sein Werk, by Alfred Einstein. (Zürich, Stuttgart 31953, S. 275-291. Permalink: www.zeno.org. Lizenz: Verwaist.)

_______________________________________________________________

Part 3 covers piano sonatas 7-13 (K. 309-311, and 330-333.) Recordings are available through the following links:

Mozart – Piano Sonata No. 7 in C, K. 309

Sonata No. 8 in a minor, K. 310

Sonata No. 9 in D, K. 311 – mvt. 1. Allegro con spirito

Sonata No. 10 in C, K. 330 – mvt. 2. Andante cantabile

Sonata No.12 in F, K. 332 – mvt. 1. Allegro

Mozart – Piano Sonata No. 13 in B flat, K. 333 – mvt. 3. Allegretto grazioso

There are also scores and recordings online in the excellent Digital Mozart Edition. (A Project of the Mozarteum Foundation Salzburg and the Packard Humanities Institute.)

___________________________________________________________________

Mozart. The Piano [3].

… The six sonatas [K. 279-284] served in Mozart’s repertoire as a virtuoso soloist for a surprisingly long time – even the weaker pieces. He performed all of them repeatedly on the long journey of 1777/78 to Mannheim and Paris. Yet while in Mannheim the need arose to expand his repertoire, and so from November 1777 to late summer 1778 he composed seven new sonatas. These new works were no less individual and kaleidoscopic than the previous grou0p. Two of these, K. 309 in C and K.311 in D, should be called the Mannheim sonatas, as both were completed there in 1777.

We are especially well informed about the emergence of the first sonata. Mozart improvised the work in his last Augsburg concert, on Oct. 22; or, more exactly, the first and last movements, with a different slow movement. He wrote of this on Oct. 24, 1777: “Then I played … a splendid sonata in C major, conceived on the spot, with a Rondeau as the final movement. It was a really noisy affair…” [ein rechtes Getös und lerm (sic)] This is how Mozart described the outer movements, especially the rondo with its 32nd note tremolos. But he forgot to mention the subtlety the “splendid” and “noisy” work shows in its pianissimo conclusion. Both works are full of instrumental display, with the first like a Salzburg C major symphony, reimagined for one of Stein’s pianos.

The middle movement, however, an Andante un poco adagio, was not written out from memory. It was newly composed, as Mozart sought to portray the character of Mademoiselle Cannabich, the daughter of his new friend, the Kapellmeister Cannabich. Since we know nothing about this character, we cannot judge if the portrait is fitting: it is a “delicate” and “sensitive” andante, with always richer and more elaborate repetitions of the theme. And as Mozart was little given to realism, one might also view the slow movement from the other Mannheim sonata, an Andante con espressione, very childlike and “innocent”, as a portrait of the young Rose Cannabich. This other sonata is clearly a companion to the work in C; as in the first movement, the return of the principal theme is avoided in the recapitulation, and comes only as a surprise in the coda. (We know this subtle feature already from works of 1776, for example in the Divertimento K. 247.) In both works the middle register of the instrument takes on new life; where the left hand in each work is no longer mere accompaniment, but a more serious partner of the dialog. Both compositions are also concerto-like, and Mozart considered them as among his most difficult sonatas. This is true, as also in general even Mozart’s apparently most simple works are difficult to play.

As these Mannheim sonatas are twins, so the five Paris sonatas are as different as possible. They were all – next to a row of variations, of which “Ah, vous dirais-je, Maman” (K.265) with its intentionally child-like humor is the most valuable – written in the tragic summer of 1778. And the first, in a minor (K .310), really is a tragic sonata, a companion to the sonata for violin and piano in e minor (K. 304) that had just appeared. Yet as this e minor is lyrical, not averse to rays of light falling in, the other sonata is dramatic and full of relentless darkness. Not even the turn to C major at the end of the first movement’s exposition brings any relief. And in the slow movement, “con espressione”, while the development section shows consolation at first, the total impression still clings to a strange agitation until the reprise. The disquiet shows from start to finish in the shadowy presto – a disquiet despite a certain musette-like melodic flowering at the start. A minor – and sometimes also A major, in a certain sense – is for Mozart the tonality of despair. There is no “sociability” here, and the expression is very personal. One would search in vain, if looking in the entire production of this time, for anything similar. We understand the surprise of M. Saint-Foix; that this work of 1778, appearing in 1782: in Paris, the city of criticism, was silently received by contemporaries there — simply without commentary.

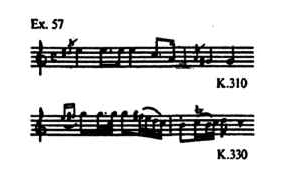

As if to free himself inwardly, Mozart wrote not only the charm-filled variations based on a children’s song, noted above, but also the sonata in C major, K. 330. There is even a thematic connection between the main theme of the a minor sonata, and a particle of the second theme of the C major work; as between darkness and clearing.

The sonata seems “lighter”, but it is a masterpiece like the others, in which every note is firmly “seated”. It is one of the most attractive works Mozart had written, in which the shadows of the Andante cantabile brighten to cloudless clarity; with an especially thrilling journey, as the second half of the finale begins with a simple tune.

The “favorite sonata” in A major (K. 331) follows: with variations at the beginning, the Rondo alla turca at the end, and the Menuetto – better, Tempo di Menuetto – in the middle, by which many received their first idea of Mozart. Yet it is an exceptional work, and really a companion to the Munich/Dürnitz sonata in D; only with the variations at the beginning, which are naturally shorter and less virtuosic, and based on a Polonaise (the most French of dance forms); which then closes with a true ballet scene. A too ardently German professor even tried to prove the “Teutonic” origin of the variation theme, but it is as French and Mozartian as possible; Mozartian above all in the strengthening of the conclusion with forte, later used for symbolic power in his setting of Goethe’s “Vielchen”. Above all, one finds the fullness and sense of resonance of the Dürnitz sonata again, only more so, with A major a heightening of D major. The minor of the Rondo alla turca here adds a mildly eerie effect.

We have already spoken of the next (and next to last) of the “Paris” sonatas, in F, as one of Mozart’s most personal works; and which should not be criticized, as having few Beethoven-like qualities. One could say of this (K. 332) and the following sonata in B flat (K. 333), that Mozart found his way back to J.C. Bach and to himself: — to Bach above all in the adagio of the F major, and in the first movement of the B flat major sonata; and to himself in the finale of K. 333, that suggests a yet more perfect duplicate, if possible, of the rondo of the K. 281 sonata, also in B flat.

J.C. Bach arrived in Paris in early August 1778, and it is impossible that he did not share his recent sonatas with Mozart. (These appeared in print as Bach’s op. 17.) Only now, this acquaintance was not made upon a less sensitive soul, but on a mature personality; on a now selective kind of mastery, that immediately transformed any suggestive offering into his own, Mozartian form. We do not know if Mozart played any of his recent piano or piano and violin works for his creative model [J.C. Bach]. He did not mention anything in letters home. It is also probable he was cautious about risking a valuable, father-like friendship.

Six years would pass until Mozart, in Vienna, again decided to write out piano sonatas, which only shows there was no immediate need to do so…

[To be continued.]

Translation by Edward Eggleston.