_____________________________________________________________________________________

Impressionism as optical realism: Monet

by Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. (See citation below.)

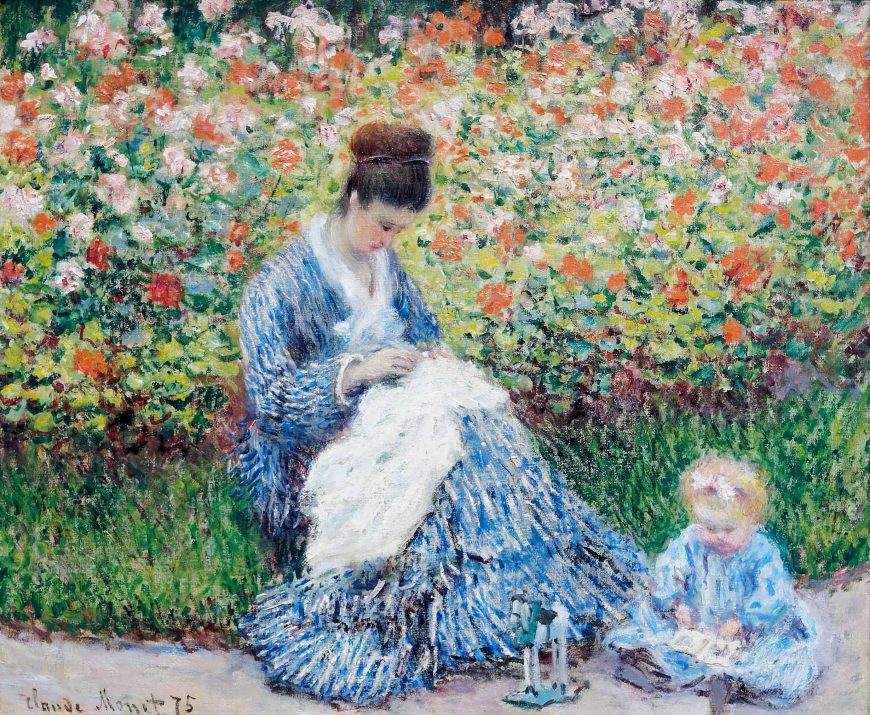

Claude Monet, Camille Monet and a Child in the Artist’s Garden at Argenteuil, 1875, oil on canvas, 55.3 x 64.7 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

More realistic?

The subject of Monet’s 1875 painting of his wife Camille Monet and a Child in the Artist’s Garden at Argenteuil is immediately recognizable. Both figures are clad in blue striped garments and are absorbed by an activity: Camille sews, the child gazes down at a book. A toy horse stands in the foreground, and a virtual wall of green foliage and blooming red and pink flowers rises behind them.

The viewer is given enough visual information to recognize the main components of the scene, but rather than supplying fine details that would provide more specifics, Monet emphasizes his brightly colored brushstrokes. If we want to know what kind of fabric the garments depicted are made of, what kind of flowers are blooming, or even the texture of the figures’ skin, we can’t find out by looking closely. Close study of the painting will only teach us more about Monet’s brushwork, not more about the depicted scene.

As a result, if we evaluate the painting’s truth to nature in terms of the careful representation of details, it is not very realistic. However, Impressionist paintings like this one were often described by sympathetic critics as realistic representations, and sometimes even as more realistic than traditional academic paintings with meticulously detailed figures and scenes. How so?

Truth to reality

Impressionism raises complex and interesting questions about realistic representation. Although we tend to have powerful reflexive judgments about what is realistic in art and what is not, the basis for such judgments is frequently unclear. Supporters of Impressionist painting subtly but substantially shifted the criteria for judging truth to reality in painting. In traditional Renaissance and Academic naturalism, truth to reality entailed the inclusion not only of what we see, but also prominent visible evidence of properties of touch and space: the mass of objects, their textures, and the three-dimensional terrain in which they are located. Because paintings cannot literally reproduce space, mass, and texture, they must give an illusion of those qualities—and they frequently exaggerate the visual evidence that contributes to that illusion.

Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, 3.3 x 4.25 m, painted in Rome, exhibited at the salon of 1785 (Musée du Louvre)

The more orthogonal lines are included in a painting, the more convincingly the ground in a painting appears to recede like a floor, rather than standing upright like a wall—hence the French Academic painter Jacques-Louis David includes a tile floor and masonry walls with many orthogonal lines in The Oath of the Horatii. Effects of chiaroscuro in traditional naturalism are also frequently exaggerated relative to what we actually see in order to assert the tangible volume of what are actually only two-dimensional renderings. The dramatic contrast created by the starkly lit figures against the very dark shadows and background in David’s painting heightens the illusion of three dimensional forms in space.

Only what we see, not what we know

The relation of figures to space in Monet’s Camille Monet and a Child in the Artist’s Garden is markedly different. There is no use of chiaroscuro to define the forms of the figures or linear perspective to define the space in which they are situated. The figures sit directly in front of the foliage, creating a very shallow space, which is further flattened by the prominent textured brushstrokes throughout the entire painting. The light source is diffused, and there is very little modeling of the figures, only a few dark areas in the clothing that distinguish the arms from the torsos.

Claude Monet, Camille Monet and a Child in the Artist’s Garden at Argenteuil (detail), 1875, oil on canvas, 55.3 x 64.7 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The Impressionist style as exemplified here by Monet consists in rendering only optical data, reproducing only what we see, not what we know about space, mass, and the other physical details of the world. In 1883, the critic Jules Laforgue suggested, “The Impressionist sees and renders nature as it is—that is, wholly in terms of color vibrations. No drawing, no light, no modeling, no perspective, no chiaroscuro, none of those puerile classifications: all these become vibrations of color and must be represented on the canvas by means of color vibrations.” There is some sleight-of-hand in this appeal to the greater truth of Impressionism, of course. Laforgue states that the Impressionist “renders nature as it is [telle qu’elle est],” but he should perhaps more accurately say that the Impressionist concentrates on rendering nature as it appears to the eyes. In this sense, the Impressionists both limited the project of painting to a narrower goal than that pursued by traditional naturalism, and increased its accuracy with regard to that goal.

Lilla Cabot Perry, A Stream Beneath Poplars, c. 1890-1900, oil on canvas, 65.4 x 81.3 cm (Hunter Museum of American Art)

Shifting patterns of color

The full import of this notion for the Impressionist approach to painting is clear in the American artist Lilla Cabot Perry’s recollection of Monet’s advice to her:

“When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have before you—a tree, a house, a field, or whatever. Merely think, Here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape, until it gives your own naïve impression of the scene before you….” [Monet] said he wished he had been born blind and then had suddenly gained his sight so that he could have begun to paint in this way without knowing what the objects were that he saw before him. Lilla Cabot Perry, “Reminiscences of Claude Monet from 1889 -1909,” The American Magazine of Art, vol. 18, no. 3 (1927), p. 120.

Monet here expresses a desire for an impossible separation of the immediate sensation of his vision from the subsequent processing of visual data by his mind. Imagine a baby’s first visual experience. She does not know that the color patterns she is experiencing correspond to substantial objects out there in a tangible world; nor does she know where one object ends and another begins; nor the distinction between near or far. An infant or a blind person suddenly gaining their sight would see only a shifting pattern of color. Accordingly, Monet advises Perry not to think about the objects that she is painting, but to see only a pattern of color: a “square of blue,” an “oblong of pink,” a “streak of yellow.”

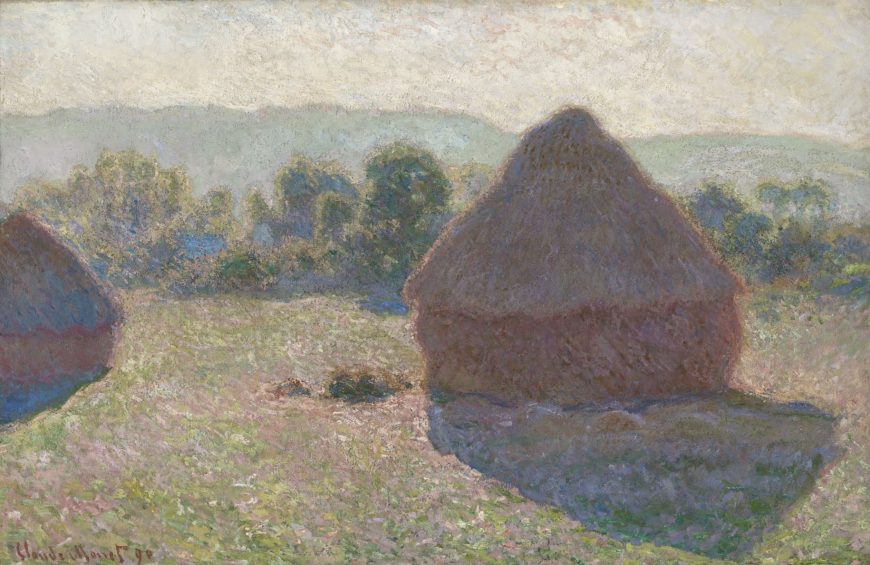

Claude Monet, Haystacks, Midday, 1890, oil on canvas, 65.6 x 100.6 cm (National Gallery of Australia, Canberra)

Painting light

Monet’s advice to Perry also begins to account for the radical brushwork of the Impressionists, which disturbed many critics. Impressionist artists constructed their paintings in color patches in the way Monet described, as though painting the optical world as they experienced it on the surface of their retinas, rather than attempting to create an illusion of the space, mass, and textures of the tactile world. Critics also observed that the patchy brushwork of the Impressionist style simulated flickering patterns of light and color. The apparent rapidity of the brushwork indicated the rapidly shifting lighting conditions, which changed before the artist had time to smooth the surface of the work with a traditional Academic finish.

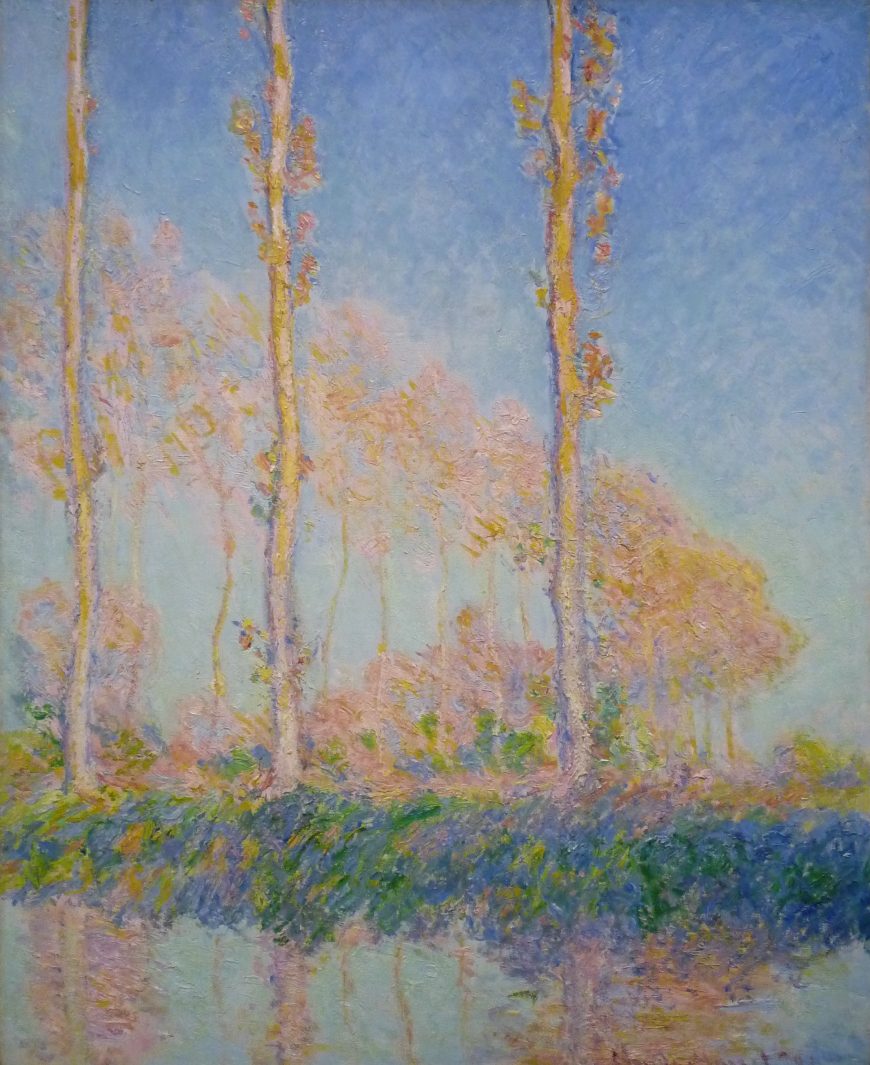

Claude Monet, Poplars, 1891, oil on canvas, 93 x 74.1 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Monet’s series paintings of the 1880s and 1890s represent the culmination of this optical-scientific aspect of Impressionism. In these series Monet recorded the changing appearance of a single subject—haystacks in Giverny, Rouen cathedral, a bank of poplars—at different times of day, in different weather, and in different seasons. Since the quality of light changed rapidly, Monet could work on a given canvas for a limited time, taking it up again only when lighting conditions were similar. Perry reported that one particular light effect in the Poplars series lasted only seven minutes, until the sunlight hit a certain leaf.

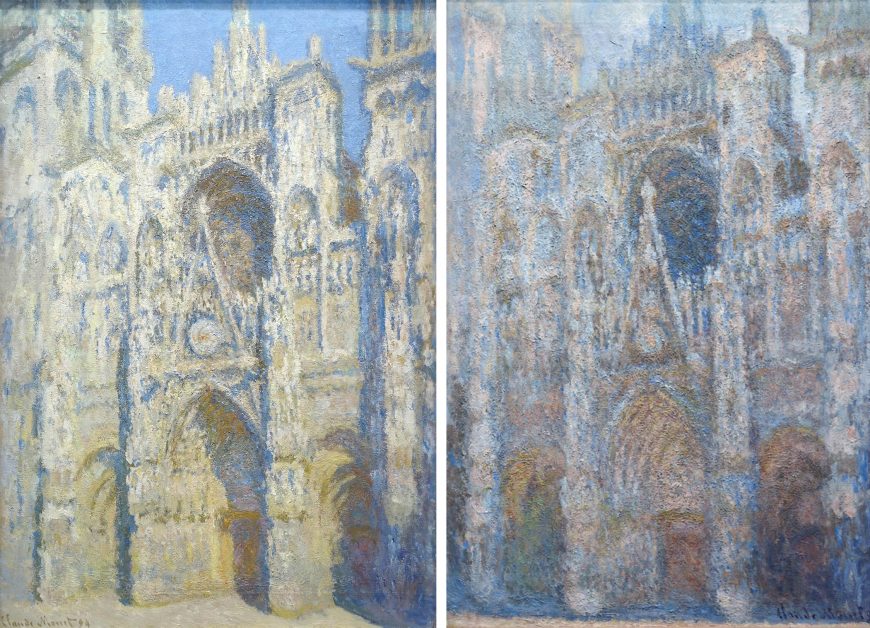

Left: Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral (The Portal and the Tour d’Albane in full Sunlight) also called Harmony in Blue and Gold, 1893 (dated 1894), oil on canvas, 107 x 73 cm (Musée d’Orsay); Right: Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral, Portal, Morning Sun, 1893, oil on canvas, 92.2 x 63.0 (Musée d’Orsay)

Although the subject matter is identical, the radically different colors used in the approximately thirty views that Monet painted of Rouen Cathedral in 1893-94 demonstrate the changes in the appearance of the scene over the course of time. Within the nominally grayish-tan local color of the masonry, Monet finds a surprising variety of colors. The first work records a painting time around noon on a sunny day, and the dominant color is bright yellow, with flickers of blue for the shadows around the carved façade. The second records an early morning observation, with the entire façade cast in shade and rendered in blues, violets, and pinks. In both works reflected light bounces up from the ground in front of the cathedral onto the underside of the deeply-carved arches of the portals, which are rendered in bright orange—very far indeed from the local color of the stone. (For an explanation of the terms “local color’” and “perceived color,” see Impressionist color.)

Living up to its name

For supporters of the movement, the name Impressionism is singularly apt, even though it was originally applied as a term of derision. “Impression” can be used as a scientific term for the stimulation of the sensory nerves, as for example the effect on the retinal nerves of light reflecting off objects. Strictly speaking, the term isolates this purely physical stimulus from any subsequent mental or emotional reaction to it. The retinal impression consists only of a pattern of colors, before the mind interprets what it is seeing and deduces information about mass, space, and texture, and before the viewer reacts emotionally. For some of its critics and practitioners, Impressionism had the aura of an objective scientific project, informed by and contributing to a wealth of contemporary discoveries in the science of light and color.

Citation: Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant, “Impressionism as optical realism: Monet,” in Smarthistory, April 15, 2019, accessed June 15, 2020, smarthistory.org/impressionism-optical-realism-monet/.