Crime stories in this genre often highlight the life of a crime figure or a crime’s victim(s). Or they glorify the rise and fall of a particular criminal(s), gang, bank robber, murderer or lawbreakers in personal power struggles or conflict with law and order figures, an underling or competitive colleague, or a rival gang. Headline-grabbing situations, real-life gangsters, or crime reports have often been used in crime films. Gangster/crime films are usually set in large, crowded cities, to provide a view of the secret world of the criminal: dark nightclubs or streets with lurid neon signs, fast cars, piles of cash, sleazy bars, contraband, seedy living quarters or rooming houses. Exotic locales for crimes often add an element of adventure and wealth. Writers dreamed up appropriate gangland jargon for the tales, such as “tommy guns” or “molls.”

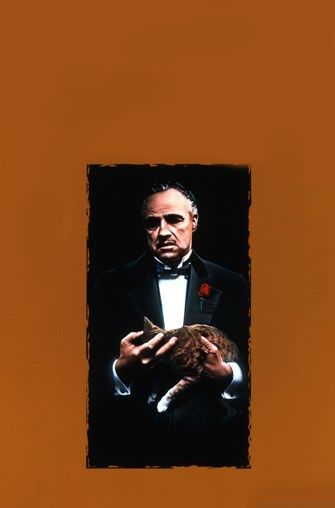

Film gangsters are usually materialistic, street-smart, immoral, meglo-maniacal, and self-destructive. Rivalry with other criminals in gangster warfare is often a significant plot characteristic. Crime plots also include questions such as how the criminal will be apprehended by police, private eyes, special agents or lawful authorities, or mysteries such as who stole the valued object.

The 1920s decade was a perfect era for the blossoming of the crime genre. It was the period of Prohibition, grimy and overpopulated cities with the lawless spread of speakeasies, corruption, and moonshiners, and the flourishing rise of organized gangster crime.

It wasn’t until the sound era and the 1930s that gangster films truly became an entertaining, popular way to attract viewers to the theatres, who were interested in the lawlessness and violence on-screen. Many of the sensationalist plots of the early gangster films were taken from the day’s newspaper headlines, encouraging the public appetite for crime films. They vicariously experienced the gangster’s satisfaction with flaunting the system and feeling the thrill of violence. Movies flaunted the archetypal exploits of swaggering, cruel, wily, tough, and law-defying bootleggers and urban gangsters.

The coming of the Hays Production Code in the early 1930s spelled the end to glorifying the criminal, and approval of the ruthless methods and accompanying violence of the gangster lifestyle. The censorship codes of the day in the 1930s, notably the Hays Office, forced studios (particularly after 1934) to make moral pronouncements, present criminals as psychopaths, end the depiction of the gangster as a folk or ‘tragic hero,’ de-glorify crime, and emphasize that crime didn’t pay. It also demanded minimal details shown during brutal crimes.

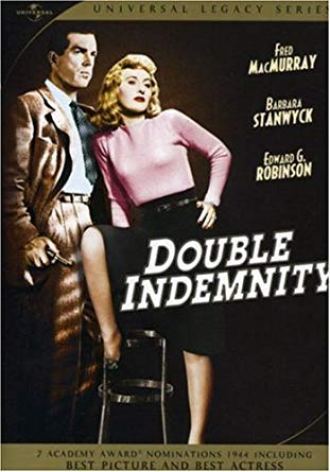

In the 1940s, a new type of crime thriller emerged, more dark and cynical – see the section on film-noir for further examples of crime films. Criminal and gangster films are often categorized as post-war film noir or detective-mystery films – because of underlying similarities between these cinematic forms. Crime films encompass or cross over many levels, and may include at least these different types of films: the gangster film, the detective (or who-dun-it) film, the crime comedy, the suspense-thriller, and the police (procedural) film.

The Homewood Library in collaboration with OLLI, will present a series of the following American Crime Film Classics on Fridays, March 8, 15, 22 & 28, from 1-5 p.m. in the Large Auditorium